Finding the Image Between Lines and Shapes

How angles, arcs, and shapes create drawings with depth

Drawing My Way–Built on Intuition

Even as a kid, I’ve always drawn.

Picking up a pencil and building layers of graphite into an image came naturally to me. Then later, through pen or ink and wash.

But intuition only takes you so far. If you don’t adapt your technique, it becomes stale, and improvement or creative growth stagnates. I’ve never attended art school or gone the classical learning route, but that doesn’t mean I’ve never trained.

It just looked different. That odd short course on composition, online video showing a new process, reading up on artists of the past or watching others work were all my classroom and helped develop my style—one that is always changing.

One of the most transformative lessons has been treating an object not as a whole, but as a collection of shapes.

Seeing Shapes, Not Things

When I sit down to draw, I remind myself not to get lost in replicating the object before me. A chair is not a “chair” until my mind labels it so—it’s a collection of angles, arcs, and intersecting marks on the page.

The moment I forget this, the drawing slips into something stiff or inaccurate.

“Treat nature according to cylinder, sphere, and cone and put the whole in perspective…”

— Paul Cézanne[1]

This idea of focusing on the structure of what I’m drawing rather than simply trying to draw the thing really resonates with me. It simplifies complex compositions in a way that simple observation cannot do.

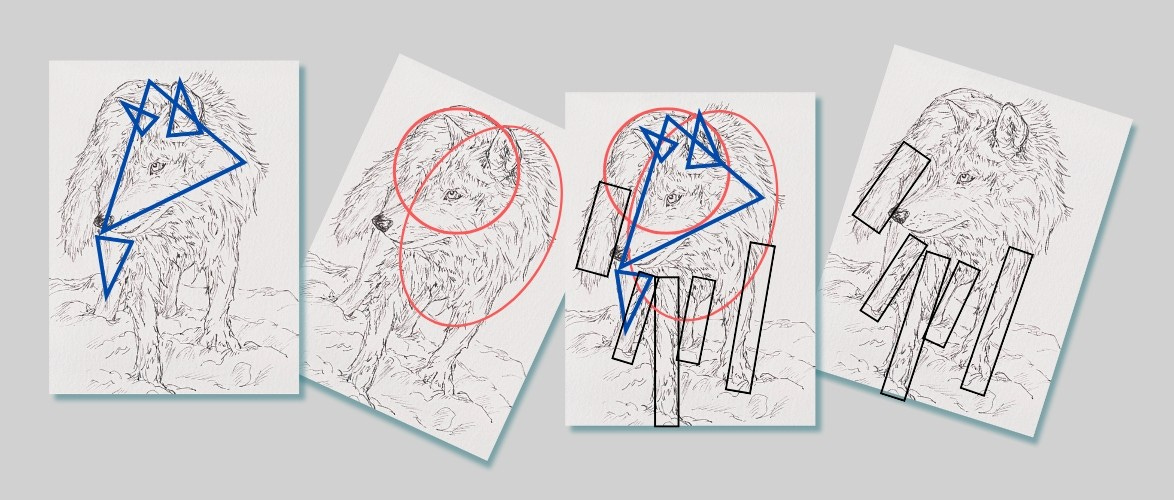

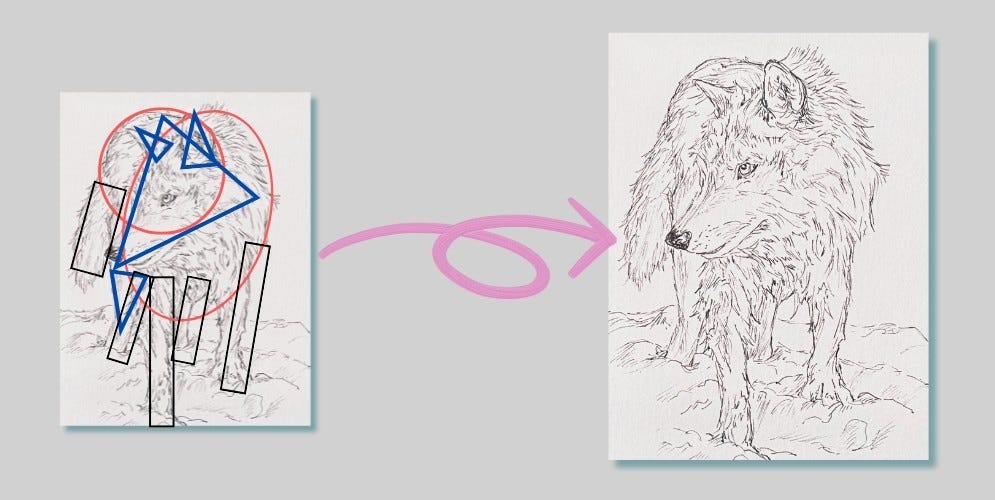

For example, the wolf I’m drawing is broken down into a series of triangles that overlay circles, ovals and oblong cylinders (see above)—and that teacup is simply ovals and half-circles that curve into one another. I start by identifying and recording the shape and then work outwards from there; I soften the edges, merge them, manipulate them until a picture finally emerges that represents the image I see.

If you’re getting value out of this why not Subscribe for future content.

But using shapes isn’t just about the shape of the subject; negative space helps too.

Often, I’ll sketch the void around a subject before touching the subject itself. The triangle formed between a person’s arm and their torso, those fragmented semi-circles created between branches of a gumtree—are often easier to render if we ignore the surrounding forms.

Regardless of whether I’m drawing the shapes of my subjects or the negative space around them, both build to develop a picture that mirrors what I see.

Not only does this practice create work that is better, more detailed, and active, but turns my observation into active engagement with my work. I’m not a passive onlooker, but I measure, compare, and delve into the relationships between form and space.

And in the end?

Starting with shapes turns drawing into a game of discovery.

I’m not just copying a chair or a wolf or a teacup—I’m chasing angles, arcs, and the gaps between them. It makes me look harder, notice more, and pay attention to the quirks and oddities that give a thing its character. Shapes let me see the world properly, not just what my brain thinks it knows.

And really, for me, that’s the fun part?

Because in art—as in life—truth often hides tucked away in spaces we ignore.

[1] Cézanne, Paul (2013). The Letters of Paul Cézanne. Translated by Danchev, Alex. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 978-0-500-23908-7.

✨ You can find some of my artwork available as downloadable prints in my Etsy store (for personal use only): christinapartstudio.etsy.com